From vacuum cleaners to AI assistants: A cautionary tale of technological promises

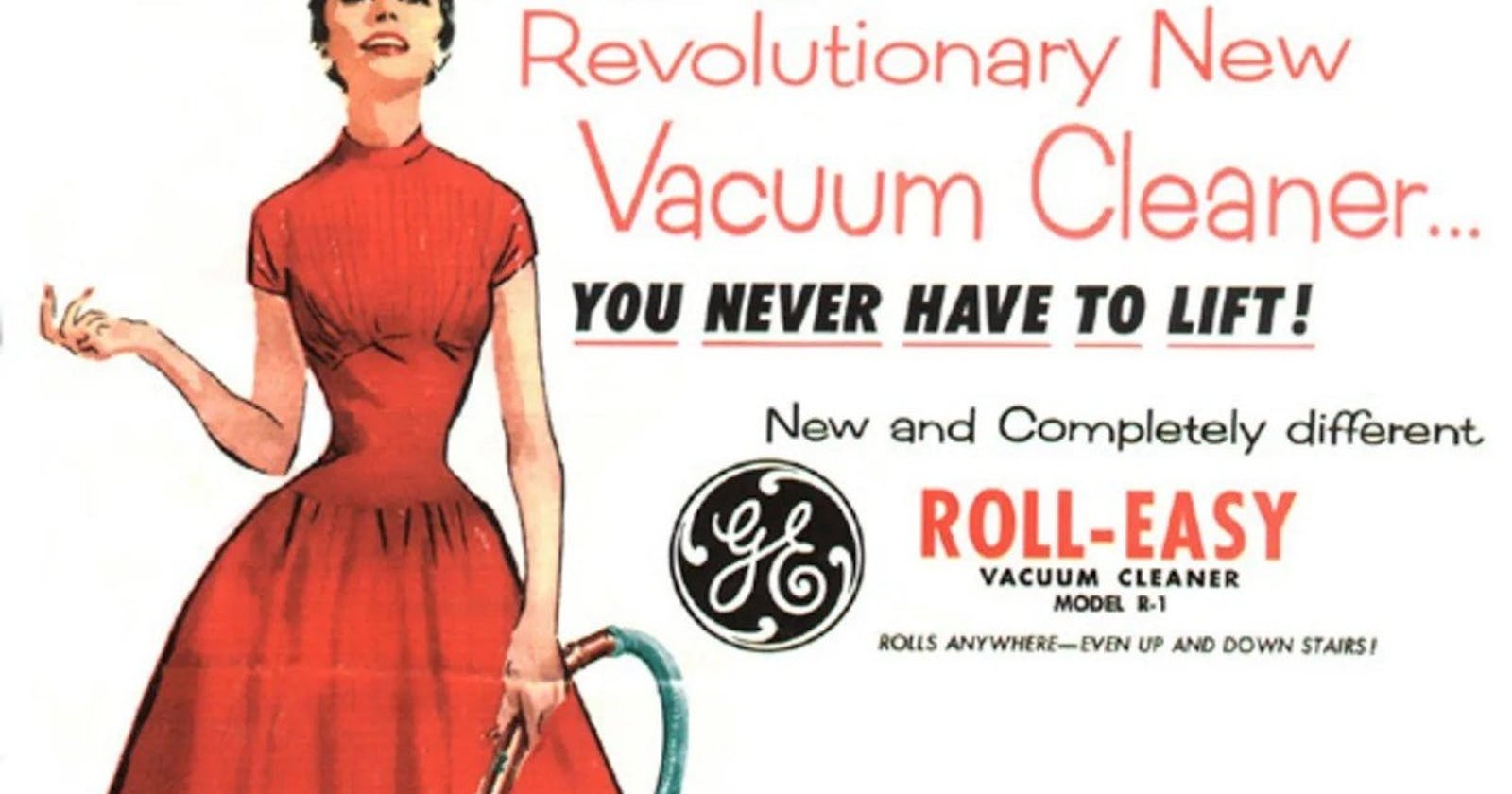

British engineer Hubert Cecil Booth, who was better known for designing suspension bridges and Ferris wheels, invented the first powered vacuum cleaner in 1901. It was a horse-drawn combustion-engine-powered suction sweeper that promised to revolutionise everyday work for housepersons.

Have you ever wished you had another set of arms for your cleaning, after over 120 years when the first vacuum cleaner came out?

We tend to assume that things like the vacuum cleaner, the electric iron, the laundry machine, etc. made life easier. These electric appliances indeed replaced processes that would previously have required time-intensive human labour. However, as a whole, these inventions did not result in there being less domestic work.

Here's the proof. Between 1912 and 1914, research had been done to find out how many hours a week women spent on domestic chores. This was before the widespread adoption of electric appliances. It was found that the average woman spent 56 hours on housework. Between 1925 and 1931, electric appliances had become standard, thanks to cheap portable electricity. Yet, the amazing thing is that research still found that women were spending between 50 and 60 hours a week on household chores. Even as late as 1965 the average was still 54 hours.

Now, fast-forward to modern times. In 2006, similar research was once again undertaken, focusing on women who chose to devote themselves to domestic work. Again, the research showed that they were still spending between 51 and 56 hours a week.

On the surface, this seems strange. Why would women in the early 21st century spend roughly the same amount of time on household chores as women in the 1910s before the advent of the vacuum cleaner, the washing machine, the dishwasher, and so forth?

The answer is that expectations changed. The standards for the amount of socially acceptable wrinkles in your blouse or dress suddenly shot up. Even children's school clothes had to be neatly ironed. Previous to this time, the idea of children needing to appear in ironed clothes would have seemed ludicrous.

The standards for how clean your house ought to be also shot up. Instead of cleaning your rugs once or twice a year, you were expected to vacuum every day.

The standards for how clean you needed to be shot up. Our idea of needing to take a shower every day, and to never wear the same underwear two days in a row, is an anomaly from the perspective of history.

Will AI follow the same trajectory?

Proponents envision AI streamlining tasks, freeing individuals from drudgery and ushering in an era of leisure. While AI automates tasks, it often breeds new challenges.

Hunter-gatherer societies like the Hadza and Batek offer a contrasting perspective. Working just 3 to 5 hours a day, they exhibit high levels of satisfaction and well-being. Their secret lies not in technology, but in a fundamental shift in values. They prioritise leisure, community, and connection. Instead of chasing an idealised version of "productive", they focus on what truly matters to them. Their example challenges the dominant work-centric paradigm and suggests that true work-life balance might not be achieved through technology alone, but by re-evaluating our relationship with work and its purpose in our lives.

By redefining work, prioritising intrinsic motivation, and appreciating the value of leisure and connection, we can strive for a life that is not merely efficient, but truly meaningful and fulfilling. This, ultimately, is the promise worth pursuing, with or without the latest technological gadget.